The campaign season is over. The fate of all candidates – presidential and parliamentary – now rests with 18 million Ghanaian voters. When all is said and done, all Ghanaians want is a free, fair, and peaceful election. As we head to the polls energized and excited, let our political temperaments be guided by this simple fact – no life is worth losing over an election.

It has been quite an interesting campaign season to observe. I have regularly shared my thoughts in op-ed pieces and media interviews. As the campaign season ends, here are five most important lessons for me.

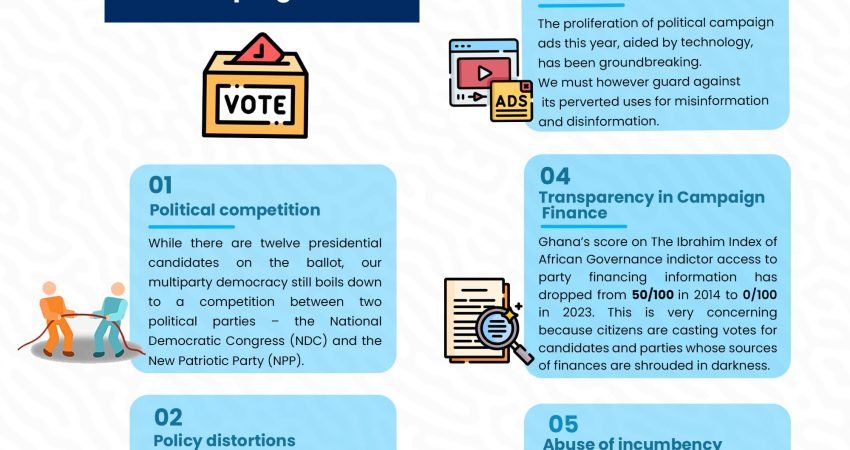

- Political competition. While there are 12 presidential candidates on the ballot, our multiparty democracy still boils down to a competition between two political parties – the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP). It begs the question whether the clamoring for alternatives to the NPP and NDC will ever materialize. Between Round 2 (2002) and Round 5 (2012) of the Afrobarometer survey, the percentage of Ghanaians saying “more political parties are needed to give Ghanaians a real choice in who governs them” increased from 56% to 81%. By Round 9 (2022) that dropped to 74 percent. In addition, our election results show that 9 out of 10 Ghanaians vote for the NDC and NPP. A trend I expect to see with this election. If this continues, it may take a while before the stronghold the duopoly has on our governance architecture is broken.

- Policy distortions. Ghanaians have a set of policy priorities they expect government to pay attention to. According to the National Commission for Civic Education’s “Matters of Concern to The Ghanaian Voter” released in October, the top three policy priorities are education, employment, and health. From Afrobarometer Round 10 (2022), unemployment, infrastructure/roads, and health emerged as the top three priorities of Ghanaians. It is the responsibility of our political parties to offer policy proposals to address these priorities. In politics, I accept that competitors strive to show the superiority of their policy ideas by discrediting those proposed by their rivals. This sometimes crosses into the territory of policy distortions through deliberate mischaracterization. There is the need, in future elections, to guard against policy distortions. Entities such as the media and civil society organizations have a responsibility to act as the guardrails against policy distortions.

- Technology and campaign advertisements. The proliferation of political campaign adverts this year, aided by technology, has been groundbreaking. The NDC and NPP found succinct ways to make their case to the electorate through such adverts. This is a positive development in our electoral politics. At the same time, the proliferation has come with failure to avoid engaging in misinformation and disinformation. As we embrace this new era in our politics, we must guard against any perverted uses of technology in creating political campaign ads.

- Transparency in Campaign Finance. The Constitution as well as the Political Parties Act 2000, provides a legal framework for financing political parties. The framework places reporting obligations on political parties and prescribes sanctions for non-compliance. Yet, there is still a lot of darkness surrounding how our political parties and especially campaigns are financed. It is time we took another look at the legal framework in place, address any loopholes, and more importantly enforce the sanctions regime for any violations. On the question of loopholes two issues need attention – limits on campaign donations, and rules focusing on candidates. Campaigns cost money, no one argues against that. What remains a worry is the lack of transparency and consequences for good governance post elections. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance from the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, has a sub-indicator (Access to party financing information) which “assesses the extent to which political parties disclose public donations within one month of being received, and the extent to which they are easily available online or at the cost of photocopy.” Out of a possible 100 points, Ghana’s score has dropped from 50 in 2014 to 0 in 2023. This is very concerning because citizens are casting votes for candidates and parties whose sources of finances are shrouded in darkness.

- Abuse of incumbency allegations. Every election year this issue comes up. Yet, there are still no clear rules and guidelines for dealing with incumbent conduct in election years. The challenge with incumbency is that governance cannot come to a halt because of elections. However, the burden incumbents face is how not turn the regular acts of governance into politically motivated campaign activities. We must find a way to deal with this before the next election.

My very best wishes to all the candidates. May the people of Ghana elect leaders who will put the country first and work tirelessly to address our socio-economic and governance challenges.

John Osae-Kwapong (Ph.D) is a Democracy and Development (D&D) Fellow at the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) and the Project Director at The Democracy Project.

John Osae-Kwapong (Ph.D) is a Democracy and Development (D&D) Fellow at the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) and the Project Director at The Democracy Project.