I have never felt so out of place simply by wearing shoes. In fact, for a solid hour or so, I was painfully aware of being the only person in the room wearing them. There I sat, like a glaring anomaly in my chunky-heeled shoes, while a cat slept a few meters away, thoroughly unimpressed by my predicament. But let me backtrack for a moment.

It was a Friday afternoon in Zogbeli, Tamale, in the Northern Region of Ghana. As part of my field visit to observe data collection for the Ghana Afrobarometer Round 10 survey, I was in a household selected for an interview. The only people present were women—something I quickly learned was that it was Friday, and the men had all gone to the mosque for Friday prayers. Here I was, “the boss” from Accra, looking every bit the official in my conspicuous footwear.

The moment I sat down on the sofa I was offered, I realized my faux pas. The field research supervisor had graciously removed his shoes, and it hit me—this is Tamale, not Accra! I should have known better. Offering to take off my shoes seemed like the next best thing to salvage some dignity, especially since I had a pair of socks on. But, in an attempt to ease my discomfort, the field supervisor quickly said, “No, no, Madam, it’s okay. Sometimes, they allow women to keep their shoes on.”

Now, we both knew that wasn’t entirely true, but he was just being polite. So, I turned to the respondent, a young woman (the respondent for the interview), and apologized profusely for not following local customs. “Should I take them off?” I asked, showing her my socks as though that would help. She stared at my shoes—no, staring at them as though they were some alien object from another planet. After what felt like an eternity, she waved dismissively, “No, Madam, keep them on.”

And so, my shoes stayed on. As the interview began, I settled into observation mode. The young mother of four responded with animated enthusiasm, answering the survey questions with passion. Even though I couldn’t understand her dialect, it was clear that she was sharing her story—one of daily struggles and economic hardship. Her small living space reflected this: a modest one-room home containing all her belongings, including the distressed old sofa I was offered to sit on. While the respondent continued the interview, her kids hovered close by, looking at my shoes with interest.

As the interview proceeded, I observed the scene around me, and my mind began to wander. The survey wasn’t about politics or vote buying (although some of those questions would be asked of the respondent down the line as the interview progressed), but sitting there, I couldn’t help but think about the larger context. In communities like this, where economic hardship is so apparent, elections often take on a different meaning. It struck me that this environment— the household’s modesty and seeming financial challenges—was likely one of the leading causes of widespread vote-buying in Ghanaian elections.

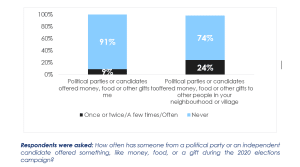

We are all too familiar with this cycle. During elections, politicians take advantage of the economic situation of individuals such as this respondent. According to CDD-Ghana’s pre-election findings from the 2020 survey, vote buying is widespread, with cash, food, and other inducements frequently utilized as payment for votes. According to the survey, nearly one in ten (9%) Ghanaians said they received some inducement in exchange for their votes during elections, including cash, food, or other gifts from political parties or candidates. Additionally, 24% of respondents said that candidates or political parties gave presents, money, or food to people in their neighborhood or village.

Vote buying is probably becoming a bigger issue, especially in places like the one I was sitting in, where poverty makes it easy for dishonest politicians to take advantage of voters.

Elections for many of these communities become more about short-term cash relief than selecting leaders based on programs or governance records. The respondent’s situation got me thinking about how political parties may easily intervene and buy votes by presenting presents or money. Her vote becomes more than just a democratic right in such a circumstance; it becomes a lifeline. Politicians are aware of this.

At some point during the interview, a second woman, possibly a relative, entered the room. She poured out coins from her wooden piggy bank, carefully counting them—likely for a small purchase. It was a quiet, humbling reminder of the financial difficulties faced by these women. I couldn’t help but think of how this scene, played out in different forms across the country, contributes to the vote-buying mentality.

As I watched the children dart glances between my shoes and the adults, I thought about how elections and election campaign season are more about survival than civic obligation for many Ghanaians. Ghanaians living in poverty see these gifts from politicians as a rare chance to improve their immediate situation, even if only for a short while. During these times, survival comes first, and democracy takes a backseat. Unfortunately, the result is often the same—voters choose candidates who may do little to alleviate their long-term struggles, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and corruption.

The vote-buying culture erodes trust in the electoral process and distorts the very principles of democracy. The basic foundations of democracy are distorted by this vote-buying mentality, which undermines confidence in the democratic process. Elections no longer represent the will of the people when votes are bought; addressing this problem requires taking on poverty head-on. It ensures that Ghanaians, like the respondent interviewed in Zogbeli, have access to improved social welfare and economic prospects to lessen the temptation of easy money during elections. It also entails educating voters so they may make decisions based on the long-term goals for their communities in particular and Ghana in general rather than on immediate financial benefit.

As I left that room after a good hour and forty-five minutes, shoes still on, I realized how this experience told a much larger story about the state of democracy in Ghana. It’s a story of how poverty, politics, and the power of a few coins can shape the future of a nation.

Author

Edem Selormey (PhD) is the Director of Research at the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana).